Exactly one year ago, eight governors across the US took the initial move to close bars and restaurants, and the Dow Jones posted its largest one-day drop ever, finishing down a record 2,997 points. The world as we knew it was hitting the proverbial fan. New incoming information —none of which was encouraging — came across our screens at a frantic pace, causing our stomachs and portfolios to drop in tandem.

With a full year now passed by in the COVID economy, the universe of uncertainty has thankfully compressed. While it was not an advanced degree that any of us had applied for, the pandemic has imparted a lifetime of lessons, offering clear clues about the future of commercial space demand and the ways we as humans interact with the built environment.

Macroeconomy

Starting first with the economy as a whole, I know we have all become a bit numb to sideways numbers during the past year, but to dig ourselves out of this hole, it is important to understand just how deep we are. Early last year, while we were all still finishing our champagne and settling in after the holiday season, the Congressional Budget Office released its estimates of 2020 economic growth, serving as a reliable benchmark of where the economy would have stood without the pandemic. Actual output last year fell short of the CBO’s early 2020 forecast by $1.2 Trillion Dollars, good for an average loss of $3,560.06 for every American.

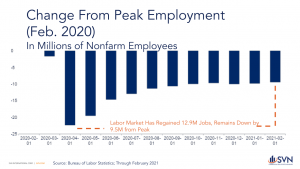

More workers filed for initial unemployment claims in the first nine weeks of this crisis than during the entirety of the 2007-2009 recession, and the unemployment rate hit a stratospheric high of 14.8% last April. Through the most recent Jobs report, it looks like we are once again starting to see some positive momentum toward an eventual recovery. The civilian unemployment rate ticked down 6.2% through February as the economy added back 379,000 jobs. We remain a long way to go, but between vaccination rollout and the onset of warmer weather, the W-shaped recession we have seen so far should have enough fuel in the tank to prevent another near-term downturn.

Multifamily

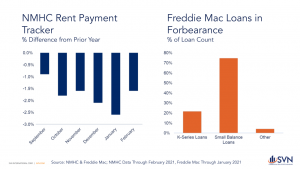

An often-peddled refrain during the early days of the pandemic was that the multifamily, and apartment sector as a whole, would maintain its stability by the simple fact that people will always need somewhere to live. If anything, the same optimists argued that the resiliency of cashflows could actually improve as renters were spending more time in their homes due to involuntary quarantines. With a year of data available now supplanting conjecture, we find that residential rentals have indeed performed up to expectations. No, conditions have not been ideal, and distress is not too hard to find, especially in gateway markets. However, compared to worst-case scenarios, the apartment sector has lived up to its reliable bedrock status. According to the National Multifamily Housing Council’s rent tracker, which follows the performance of more than 11 million professionally managed apartments, 93.5% of renter households paid rent in February— only a 1.6% drop off from the same month last year. These data may, however, likely understate some sector-level underperformance, as they do not include vacant units or self-managed “mom-and-pop” properties. According to Freddie Mac’s latest forbearance report, we know that small balance originations, which tend to cater to the “mom-and-pop” investor class, make up 75% of loans in forbearance.1

The CDC’s eviction moratorium remains a pressing challenge for the industry and an impediment to its return to pre-pandemic health. The market for rental housing is a circular flowing ecosystem between lenders, investors, and renters. There is no net-positive corrective policy that achieves more benefit than harm by breaking the symbiotic process, much as the moratoriums have. The NMHC offers that moratoriums “fail in their purpose of addressing renters’ underlying financial distress” and “jeopardize the stability of housing providers and the broader housing market.” Despite two different federal judges ruling against the CDC policy in the past month, the ban remains in place. There are, however, green shoots forming, which could signal a return to more normal conditions in the near future. At the end of this month, the moratorium is scheduled to expire— a deadline that we should accept with a coarse-grained piece of salt. Nevertheless, the appropriations bill passed at the end of the year, and the American Rescue Plan of 2021 passed last week collectively set aside $46.6B for rental assistance programs. A CPPB analysis of Census Bureau survey data finds that roughly one-in-five renter households are behind on rent— a crisis that should see meaningful relief as funds are released.2

The permanence of COVID-induced migration will be a hot-button topic as more jabs land in arms. Taken together, the trifecta of New York, California, and Illinois, the states that are home to the three largest US cities, collectively lost more than 275,000 residents in 2020. The human density that has historically attracted demand toward superstar cities has had the complete opposite effect in the past year. Without accessible cultural amenities or the need to be in an office Monday through Friday, a significant share of the workforce became untethered to their home cities and have made their way toward the exit. According to CoStar, New York, LA, San Francisco, Chicago, Seattle, Boston, and Washington DC are all among the list of cities to post year-over-year declines in asking rents through Q4 2020.

While the outgoing flow of residents has been lumped together as one homogenous cohort, there appear to be at least two major groups leaving. The first group of COVID-nomads is defined by those that already had eyes towards more affordable and spacious housing options over the next couple of years. Given the urban context in 2020 and the attractively low borrowing costs, many of these renters simply said, “Hey, why not now?” and moved up their progression timeline. These are the types of households that are more likely to be buying baby carriages before the next time they step on a subway, and their transition out of major metros is probabilistically permanent. The second group contains those who are transient, often early into their careers, working remotely, and still seeking the lifestyle amenities they had enjoyed pre-covid. Watching how this group behaves as large companies start calling workers back into the Office and cities look more like their pre-pandemic selves will be telling.

Office

Today, there is no property type subject to more speculation than the Office.

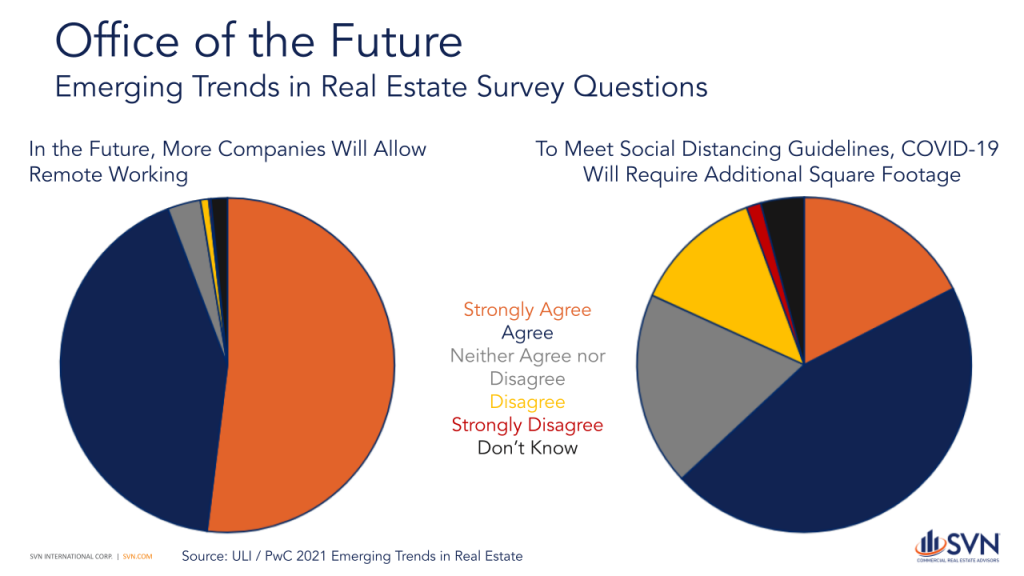

Unlike multifamily, Retail, and industrial, where COVID has mostly magnified pre-existing trends, the pandemic has led to rampant reimagination in the office sector. Our understanding of how both firms and workers interact with physical office space to optimize productivity is permanently changed. According to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, an estimated 38% of working American adults have transitioned to remote work in some capacity due to COVID. The share is even higher in large office markets like New York and Los Angeles, rising to 47% and 45%, respectively. En Masse, The American Workforce traded morning commutes for Zoom links, an illuminating natural experiment that has challenged the Office sector’s core-assumptions. When PwC launched its remote work survey in June, 44% of employers thought that the transition to remote work has allowed their teams to be more productive than before the pandemic.3 When the same employers were polled again in December, the share climbed to 52%, indicating that not only has a consensus emerged, but that efficiency has improved following the initial learning curve. The realization that companies can not only maintain but actually improve performance through a remote infrastructure is a ‘no turning back,’ Pandora’s box type of moment. It should therefore come as no surprise that, according to the same survey, only 21% Of US executives think that a full five days in the office every single week is the best setup to maintain a strong corporate culture.

The likelihood that total office space demand will have a smaller footprint in the post-pandemic world is a consideration that we cannot afford to take lightly. A Fitch research report released just last week estimates that an additional 1.5 work-from-home days per worker would lead to a 15% reduction in property-level net cash flow— a development that would meaningfully recalibrate our understanding of risk and value. Given the long-dated lease structure common throughout the sector, it will take a few years for emerging preferences to filter through fully. Moody’s Analytics REIS forecasts that vacancy rates are likely to rise to near-record levels through 2023 before beginning a gradual recovery in 2024.

Of course, not all metro-level office markets will move as one. Some of the migratory demand that is leaving large cities and contributing to localized weakness ahead will also lead to strength in other markets, particularly in major Metro adjacent suburbs. According to Real Capital Analytics, Central Business District-located Office properties posted a 0.2% decline in value for the year. On the other hand, suburban located office assets saw valuations continuing to grow at a healthy 6.6%.

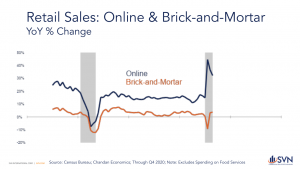

Industrial

The industrial sector remained the undisputed top performer of commercial real estate through an otherwise challenging 2020. Secular tailwinds, such as e-commerce adoption, grew from a healthy gust to a sustained hurricane force. Over the past decade, online retail sales have increased by an average of 15.2% annually. Brick and mortar retail sales over the same period have only grown by an average of 3.4% per year. The share of total Retail sales satisfied by online orders has steadily risen, entering 2020 At 11.3%. In the second quarter, as nonessential retailers across the country closed their doors, this share skyrocketed above 16%. While the share has reverted down to 14%, the pandemic has permanently transitioned some in-person retailing onto online platforms. Online grocery delivery services, a concept that had faced greater consumer resistance than other E-platforms before 2020, stood uniquely positioned to benefit from the demands of a lockdown economy. According to grocery e-commerce specialist Mercatus and research firm Incisiv Projects, online grocers accounted for 3.4% of all US grocer sales in 2019, before swelling to 10.2% in 2020.4 Further, the same study estimates that online groceries will satisfy 21.5% of domestic demand by 2025. Surging demand for E-grocers also means an increased demand for distribution and fulfillment facilities in close proximity to consumers. In the most recent Emerging Trends in Real Estate report, fulfillment facilities ranked as the subsector with the best prospects for future investment and development opportunities.

Another source of new industrial demand can be traced to the supply chain disruptions experienced this last year. The pandemic exposed critical sensitivities, and e-commerce retailers are looking to better safeguard their ability to match inventory supply with order demand. Doing so has meant a transition away from “just in time” distribution models in favor of “just in case” models instead. The latter requires excess warehousing space to stock contingent inventory.

Retail

There was no shortage of pessimism surrounding the retail sector heading into 2020, even before there was a pandemic to contend with. Pre-pandemic, Retail was in the midst of what was widely expected to be a 10-year shakeout and a painful rightsizing process. As noted in the 2021 ULI / PwC Emerging Trends Report, the US retail sector had three major headwinds going into last year: the US has more retail square footage per capita than any other country in the world, an increasing share of core-retail activity has transitioned online, and domestic consumers have experienced a long-term stagnation of wages. Concepts that were on the path towards obsolescence, with hopes of maybe squeezing out a few more years of economic solvency, are those that have struggled the most during COVID— none more so than department store retailers.

While the outgoing companies will argue otherwise, a case can be made that 2020’s pain will help the retail sector pave a quicker path back to recovery. The sector has gone from Darwinism to ‘Darwinism on steroids.’ Though, before we can imagine a radical future where physical retail demand sits just a bit higher than supply, the existing glut of obsolescent space needs to find adaptive reuse. After all, not every struggling mall will be turned into an Amazon distribution center. Lifestyle centers, where fitness centers, housing units, and mixed Retail are blended together, are one of the leading concepts to aid in re-positioning and re-absorption. According to Real Capital Analytics, Lifestyle Centers have an average price per square foot that is almost three times higher than average assessed for Mall assets, reflecting some of the value that can be recaptured through re-positioning.

As Retail continues to match physical footprints with the forward-looking consumer behavior, the short-term reversion back to normalcy will at least provide some much-needed relief. Cabin-fever-consumers armed with unspent stimulus checks should give Retailers a potent shot in the arm, even if the upside effects are only temporary.

Outlook

Whether it be the public health front, the economy, commercial real estate, our lives in general, or how all the above are inexorably linked, 2021 has all the makings of a year defined by recovery. The Federal government’s push to have vaccine availability for every US adult by May 1st means that herd immunity is not too far behind.

Between the safe resumption of our pre-pandemic lives, the commitment by the Federal Reserve to maintain low interest rates even as inflation pressures rise, and the unprecedented level of stimulus in the hands of consumers, a perfect storm of economic momentum is brewing just offshore. If anything, there is increasing concern that the economy has the potential to overheat in the year ahead as too much fuel enters the fire all at once. According to the February and March iterations of the Wall Street Journal’s Economic Forecasting Survey, a majority of leading economists believe that this year will have more upside risk than downside risk, and more than 80% think that the newly passed stimulus will generate inflation higher than the Fed’s 2% target.

In many ways, we as an industry remain in wait-and-see mode, with questions over a return to the office timing and rightsizing are still swirling overhead. Although, overly conservative and reactive strategies rarely make winning formulas in Real Estate. Now is the time for landlords to engage tenants and companies to engage employees about emerging preferences, then execute on a strategy. If 2020 has taught us nothing else, it’s that the pace of change can accelerate quickly, and falling behind the curve of innovation is a costly and often un-correctable mistake.

Endnotes

1. https://mf.freddiemac.com/docs/January_forbearance_report.pdf

2. https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/housing-assistance-in-american-rescue-plan-act-will-prevent-millions-of-evictions

3. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/library/covid-19/us-remote-work-survey.html

4. https://www.supermarketnews.com/online-retail/online-grocery-more-double-market-share-2025